If you live anywhere in the Bay Area and haven’t yet been to see the David Hockney exhibit, A Bigger Exhibition, currently at San Francisco’s DeYoung Museum, stop reading this right now and go. It’s absolutely wonderful. And for those of you not fortunate enough to live in the San Francisco Bay Area, there’s plenty here to read about and explore online.

The exhibit includes 400 of his more recent works in many mediums, leveraging many methods – oils, cameras, water colors, charcoal, video, and iPads. Portraits of friends and family, portraits of museum guards, landscapes, and nature scenes from his childhood home in Yorkshire.

His use of multiple digital cameras and iPads is remarkable. Hands-down, my favorite part of the exhibit was a room hung with large iPad replicas. On the screens were various pictures Hockney created using the iPad app, Brushes. On some of the screens you watch as the image emerges (as if on fast forward), layer by layer, color by color. I watched a bowl of peaches grow from a rough sketch to a fully dimensional, bowl of glowing orangey-yellowey-red orbs, so real I felt I could reach out and eat one. I must have watched that progression through six times, studying the way the picture progressed – color applied, color removed, color blended or smudged, jumping from one part of the painting to another, testing and retrying, layering. It was absolutely fascinating. When do you ever get to watch, time-lapse fashion, the creation of art from blank canvas to finished piece? As you can see in this photo, my fellow museum goers were similarly fascinated. A thick knot of people stood for the longest time – rapt.

As you gaze at these recorded pictures, it becomes clear that Hockney works very quickly. In this Spencer Michael’s interview with the artist, Hockney says “any draftsman knows about speed, you can see the speed in Rembrandt’s drawings. I think most painters paint faster than they will tell you.” He calls the iPad a “terrific new medium – much better than Photoshop or other digital tools. You can be very fast on an iPad, faster than watercolor.”

I was particularly struck by Hockney’s full command of the technology. Not only did he master the printing methods of high-resolution imagery, multi-camera videos, and printing (many of the iPad creations were printed out on huge sheets of paper and put together like puzzles), but his full command of the Brushes application. For instance, in one iPad painting of Yosemite, he seemed to create a stippling effect and then capture (save?) it and re-use it, much like a stamp, thereby creating a forest of pine trees here, here, and here. Quite apart from how impressive and beautiful the paintings were, the 76-year old Hockney dispels any thoughts we might harbor about digital tools being only for younger generations.

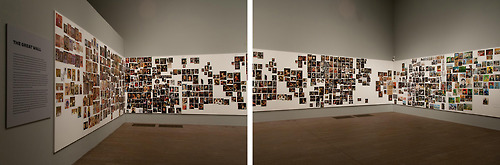

When you’re there, don’t miss the portion of the exhibit on the main floor (the exhibit is divided in two parts). Here you’ll find one of the more fascinating artifacts of his research and work – the Great Wall. Created originally in his studio, it’s been recreated here for us to wander and absorb. On the wall, they’ve pinned 100’s of high-resolution, color print outs of classic paintings, hung in order of their creation, from Byzantine art to Van Gogh – a sort of painting timeline. Hockney created the wall in order to sit back, scan and absorb centuries of western painting in one go. To see them juxtaposed and collected. He crafted an order to the collection – Northern European paintings at the top, Southern Europe at the bottom – and looked for patterns. As he studied the timeline, an order began to emerge. He realized that at about 1420, there was a big change in western painting. At that point, it appears that artists could “suddenly” draw better. The images were clearer, more exact, with strong contrasts, more three dimensional. One could even say, the paintings had more of a photographic look. Hockney’s explanation for this sudden change is that artists began to use optic lenses to create their images.

One of the paintings on the Great Wall (by Lorenzo Lotto c.1545 – hanging in The Hermitage), shown here, gave clues to the artist’s use of a lens to create his painting. Note the elaborate red cloth in the foreground, with a geometric design. When examined closely, Hockney noted an area of the cloth that is out of focus. A physicist friend of Hockney’s, Charles Falco, was able to use the size of the out-of-focus area to confirm that a lens had been used and to calculate the focal length and diameter of that lens. By using a lens to create the realistic looking cloth, the artist has to contend with a problem of geometric optics. When the focus moves from foreground to background, the scale changes. Placed together, the two halves don’t match and so the artist is forced to paint that area of mismatch out of focus.

Hockney used this information to support his speculation that these 15th century painters made use of optics to create more realistic, life-like paintings. But of course high quality large lenses weren’t available in this period of history. Falco explained that curved mirrors could serve as a lens – and curved mirrors were certainly available. As you use the mirror to focus the sun’s rays, you form an image. And if that image is aimed at a surface upon which the artist will draw, the artist will see the scene and the drawing surface simultaneously, allowing them to duplicate the key points of the scene and accurately render the precise perspective and detail. Interestingly, the size of the sweet-spot image produced by a curved mirror is roughly 30 cm square – and that’s about the size of many of early Netherlands portraits at that inflection point. This sort of optical device is know more commonly as a camera lucida. Interestingly, there is now a Camera Lucida app for the iPad and the iPhone (I wonder if Hockney knows about that?).

In 2006, Hockney wrote a book, that later became a BBC television series, called Secret Knowledge in which he delves into this theory in great detail. Of course, the theory is not without controversy. Some art historians take issue with Hockney’s explanation, claiming that the use of optical lenses has little value in explaining the overall development of western art. But it doesn’t seem that is Hockney’s claim. Using optical lenses of any variety would only be useful aids to someone who already was a skillful artist and would only be one tool in their impressive toolbox, relatively useless without the other skills they would need to render a breathtaking work of art. Besides, isn’t it delightful to contemplate the beautiful union of art and science implied by the idea?

All in all, a thoroughly satisfying exhibit. Well worth a trip.

1) Seeing the art created, I was prepared to see the role of layering, but surprised with the seemingly equally important of subtraction– taking away sketch lines and color.

2) While creating a single larger canvas, printout, or screen were available, Hockney instead chose to segment the whole delivering a different esthetic, image, and message.

3) Is the use of science to create “better” art dishonest? If not, why was its use not divulged?